Acid-Reducing Medications: How They Interfere with Other Drugs

Acid-Reducing Drug Interaction Checker

Check Your Medications

Most people take acid-reducing medications like omeprazole or famotidine for heartburn or ulcers without realizing they might be quietly sabotaging other drugs they’re taking. These medications don’t just calm stomach acid-they change how your body absorbs a surprising number of prescription drugs. For some, this means their blood pressure meds stop working. For others, their HIV treatment fails. And in many cases, neither the patient nor the doctor ever connects the dots.

How Acid-Reducing Drugs Work (and Why It Matters)

Proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) like omeprazole and esomeprazole, and H2 blockers like ranitidine and famotidine, work by lowering stomach acid. That’s their job. But stomach acid isn’t just there to digest food-it’s a gatekeeper for drug absorption. When acid levels drop from a normal pH of 1-3.5 up to 4-6, it changes the chemical state of many medications.

Most oral drugs are either weak acids or weak bases. Weak bases-like atazanavir, dasatinib, and ketoconazole-need acid to dissolve properly. In a low-acid environment, they stay in their non-ionized form, which doesn’t dissolve well. The result? The drug doesn’t get absorbed. It just passes through your gut and out of your body.

It’s not just about the stomach. While most drugs are absorbed in the small intestine, dissolution often starts in the stomach. If a drug doesn’t dissolve there, it won’t be ready to absorb later. Even if the drug eventually reaches the intestine, the delay or incomplete dissolution can mean your body gets only half-or less-of the dose you took.

Which Drugs Are Most at Risk?

Not all drugs are affected equally. The FDA identifies about 15 commonly prescribed medications with serious, documented interactions. The worst offenders are weak bases with a narrow therapeutic index-meaning small changes in dose can lead to treatment failure or toxicity.

- Atazanavir (HIV treatment): When taken with a PPI, its absorption drops by 74% to 95%. Patients have seen their viral load jump from undetectable to over 12,000 copies/mL after starting omeprazole.

- Dasatinib (leukemia drug): Absorption falls by about 60%. A 2023 study of over 12,000 patients found those on PPIs had 37% higher rates of treatment failure.

- Ketoconazole (antifungal): Absorption drops 75%. Many patients end up with no antifungal effect at all.

- Dasiglucagon (for low blood sugar): A weak acid, so its absorption actually increases slightly-but this rarely causes problems.

These aren’t rare cases. The FDA’s adverse event database shows over 1,200 reports of therapeutic failure linked to acid-reducing drugs between 2020 and 2023. Atazanavir, dasatinib, and ketoconazole account for more than half of those reports.

PPIs vs. H2 Blockers: Not All Are Equal

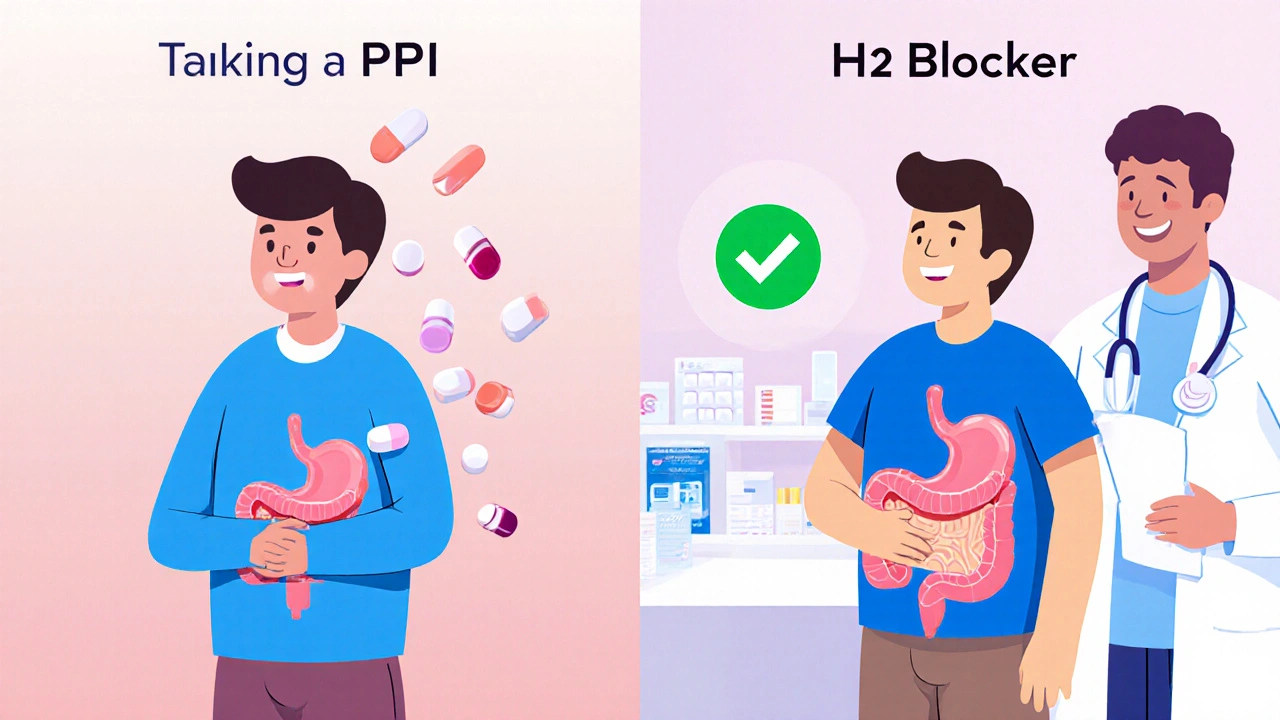

Not all acid-reducing drugs are created equal when it comes to interactions. PPIs are stronger and longer-lasting. They keep stomach pH above 4 for 14 to 18 hours a day. H2 blockers? They only do it for 8 to 12 hours.

A 2024 study in JAMA Network Open found PPIs reduce absorption of pH-dependent drugs by 40-80%. H2 blockers? Only 20-40%. That’s a big difference.

Take atazanavir again. The prescribing information says: Do not use with PPIs. But it doesn’t say the same about famotidine. In some cases, switching from a PPI to an H2 blocker can restore drug levels-though even then, timing matters.

Enteric Coatings and Other Hidden Risks

Some drugs are designed with enteric coatings to protect them from stomach acid. That’s meant to help them survive until the intestine. But when you raise stomach pH, those coatings can dissolve too early. The drug then gets exposed to acid in the wrong place-or worse, it dissolves in the stomach and gets destroyed before it can be absorbed.

This is especially true for older formulations. Newer versions of some drugs are now being developed without pH-dependent absorption in mind. But for now, if you’re on a drug with an enteric coating and you start a PPI, talk to your pharmacist. It might not be safe.

Real-World Consequences

One Reddit user wrote: “My viral load went from undetectable to 12,000 after starting Prilosec for heartburn.” Another said: “My doctor didn’t tell me Nexium would interfere with my blood pressure meds-I was consistently 20 points higher until we figured it out.”

These aren’t outliers. A 2023 study found that patients taking dasatinib with a PPI had significantly higher rates of cancer progression. In HIV patients, viral rebound from these interactions can lead to drug resistance-making future treatments harder.

And it’s not just patients. Doctors miss these interactions because they’re not taught to think about pH. A 2023 study in the Journal of the American Pharmacists Association found that when pharmacists reviewed medication lists, they cut inappropriate ARA co-prescribing by 62%.

What Can You Do?

If you’re on an acid-reducing medication and another prescription, here’s what to do:

- Check your meds. Look up your drugs on Drugs.com or Medscape. Search for “acid-reducing interaction.”

- Ask your pharmacist. They see these interactions daily. They’re trained to catch them.

- Don’t stop your acid reducer without talking to your doctor. But do ask: “Is there a safer alternative?”

- Try staggered dosing. For some drugs, taking the medication 2 hours before the acid reducer helps. But this only cuts the interaction by 30-40%. It’s not a fix-just a partial workaround.

- Consider switching. If you’re on a PPI long-term, ask if you really need it. The American College of Gastroenterology says 30-50% of chronic PPI users don’t have a valid reason for taking them.

Antacids like Tums or Maalox can be used as short-term alternatives because they work fast and wear off quickly. But you’d need to take them 2-4 hours apart from your other meds. Not practical for daily use.

The Bigger Picture

Over 15 million Americans take PPIs daily. About 15% of adults in the U.S. use acid-reducing drugs long-term-often for years, without regular review. The FDA estimates that inappropriate use of these drugs leads to $1.2 billion in wasted healthcare spending every year due to failed treatments, hospitalizations, and repeat prescriptions.

Pharmaceutical companies are starting to respond. Nearly 40% of new drugs in development now avoid pH-dependent absorption by using new delivery systems. But for now, millions of people are on older drugs that are vulnerable.

Electronic health records now flag dangerous combinations. Epic Systems reports that 78% of doctors follow those alerts. But that still means 1 in 5 don’t. And if you’re not on a system with alerts? You’re on your own.

There’s no magic fix. But awareness changes outcomes. A patient who knows to ask about drug interactions is far less likely to end up with a failed treatment or a preventable health crisis.

Can I take antacids instead of PPIs to avoid drug interactions?

Antacids like Tums or Rolaids can be safer short-term options because they don’t last long-they neutralize acid for 30 to 90 minutes. But you’d need to take them 2 to 4 hours before or after your other medication. This isn’t practical for daily use, especially if you need acid control all day. They’re better for occasional heartburn, not chronic conditions.

What if I’m on a PPI and my doctor prescribes a new drug?

Always ask: “Will this interact with my acid reducer?” Even if your doctor doesn’t mention it, bring up your current meds. Many drugs-especially HIV, cancer, and antifungal treatments-have clear warnings. If your doctor isn’t sure, ask them to check a drug interaction checker like Lexicomp or Micromedex.

Are H2 blockers safer than PPIs when taking other medications?

Yes, generally. H2 blockers like famotidine cause less pH elevation and for a shorter time. Studies show they reduce drug absorption by about half as much as PPIs. If you need long-term acid control and are on a high-risk medication, switching from a PPI to an H2 blocker might help-especially if you can space out doses. But it’s not risk-free.

I’ve been on omeprazole for years. Should I stop?

Don’t stop suddenly. But do ask your doctor if you still need it. Many people take PPIs long-term for symptoms that never needed it in the first place. The American College of Gastroenterology recommends trying to stop or reduce PPIs in 30-50% of long-term users. If you’re not being monitored for GERD or ulcers, you might be able to taper off safely.

Can I take my medication at a different time to avoid the interaction?

For some drugs, taking them 2 hours before your acid reducer can help. For example, taking dasatinib in the morning and your PPI at night might restore some absorption. But this doesn’t fully fix the problem. Studies show it only reduces the interaction by 30-40%. It’s a temporary fix, not a solution. Always check with your pharmacist or doctor before changing your schedule.

What’s Next?

The future is moving toward smarter solutions. AI tools are being developed to predict drug interactions with over 89% accuracy. Some clinics are testing wearable pH monitors to track individual stomach acidity and adjust meds accordingly. And new drugs are being designed to work regardless of pH.

But right now, the best tool you have is knowledge. If you’re on more than one medication-and especially if you’re on an acid reducer-ask the right questions. Don’t assume your doctor knows. Don’t assume your pharmacist will catch it. Be the one who checks.

11 Comments

Let me guess-you’re one of those people who thinks ‘natural remedies’ fix everything? PPIs are prescribed for a reason. If your HIV meds aren’t working, it’s not the omeprazole’s fault-it’s yours for not reading the damn label. Stop blaming the drug and start taking responsibility.

bro i was on prilosec for 3 yrs n my cancer doc never said nothin. now i got a viral load of 12k. like… wtf. why dont they just put big red signs on the bottle? ‘this will kill your meds’???

This is such an important post. I had no idea my blood pressure meds were being messed with by my heartburn pill. I switched to famotidine and my numbers finally stabilized. Don’t wait until it’s too late-ask your pharmacist. They’re the real heroes.

I just found out my antifungal wasn’t working because of my PPI and I cried for like an hour. Like why does no one tell you this stuff?? I feel so stupid for not asking. Now I’m scared to take anything ever again

I’ve been on omeprazole for like 7 years because my stomach hurt after tacos and now I’m reading this and realizing I probably didn’t even need it. I’m gonna talk to my doctor about cutting back. I just want to feel better without accidentally ruining my other meds. It’s scary how little we’re told about these things. Like why isn’t this in every doctor’s office poster?

Knowledge is power. If you’re on meds, you owe it to yourself to learn how they interact. Don’t wait for a crisis. Be proactive. Your future self will thank you.

So let me get this straight-you’re blaming acid-reducing meds for drug interactions but ignoring that the pharmaceutical industry designed these drugs to be incompatible on purpose? It’s not an accident, it’s profit. You think your ‘pharmacist’ is helping you? They’re just another cog in the machine. Wake up.

The pharmacokinetic implications of gastric pH modulation on CYP3A4-mediated drug metabolism are profoundly underappreciated in clinical practice. The FDA’s adverse event reporting system is grossly underpowered to capture the true burden of these interactions. Furthermore, the lack of standardized EHR integration for pH-dependent drug alerts constitutes a systemic failure of pharmacovigilance.

Only in America do people take PPIs like candy and then blame the system when their meds stop working. In my country, you’d be on a 2-week course and then told to fix your diet. No wonder we’re broke.

OMG I just realized I’ve been taking my blood pressure med with my Tums 😱 I’m gonna call my doctor right now. Thank you for this post!! 🙏

So you’re saying I’ve been wasting money on dasatinib because I took my PPI at night? Cool. So now what? Do I get a refund? Or do I just keep paying for drugs that don’t work because no one bothered to warn me?