Dermatomyositis and Polymyositis: Understanding Muscle Inflammation and Modern Treatment Options

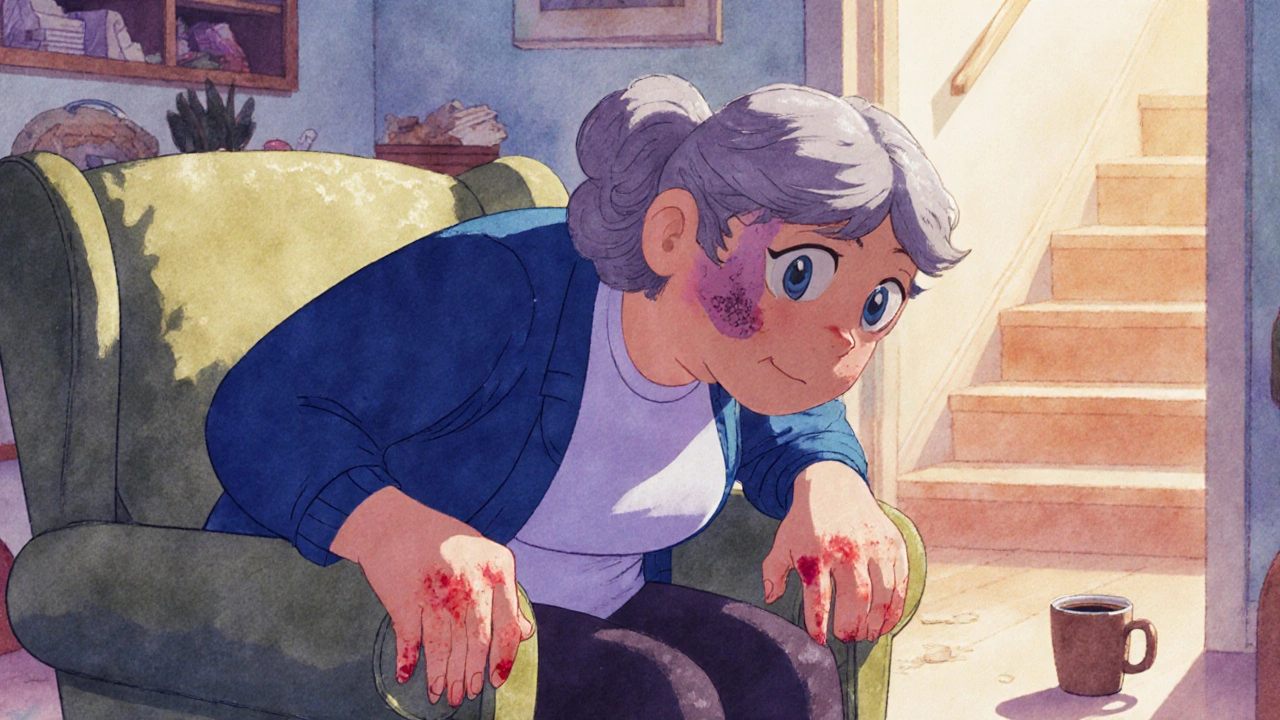

When your muscles suddenly feel heavy, and climbing stairs or lifting a coffee cup becomes a struggle, it’s easy to blame aging or laziness. But for people with dermatomyositis and polymyositis, this isn’t fatigue-it’s inflammation attacking their own body. These rare autoimmune diseases don’t just cause weakness; they steal independence, disrupt sleep, and often go undiagnosed for years. The good news? With the right approach, most people can regain strength and control over their lives.

What Exactly Are Dermatomyositis and Polymyositis?

Both dermatomyositis and polymyositis are types of inflammatory myopathy-meaning they cause chronic inflammation in skeletal muscles. These are the muscles you control voluntarily, like those in your thighs, shoulders, and neck. In both conditions, the immune system mistakenly targets muscle tissue, leading to progressive weakness.

The key difference? Skin. Dermatomyositis always comes with a telltale rash-usually a violet-colored swelling on the eyelids (called a heliotrope rash), red patches over knuckles, elbows, or knees, or a scaly rash across the chest and back. Polymyositis affects only the muscles. No rash. No skin changes. Just deep, symmetrical weakness.

These aren’t new diseases. Doctors first described them in the 1800s. But it wasn’t until the 1970s that diagnostic criteria were formalized. Today, we know polymyositis hits adults between 30 and 60, with women two to three times more likely to be affected. Dermatomyositis has a double peak: kids aged 5 to 15, and adults in their 40s to 60s. It’s rare-only about 1 in 100,000 people get it each year-but when it happens, it changes everything.

How Do You Know It’s Not Just Being Tired?

Many people mistake early symptoms for fibromyalgia, thyroid problems, or even depression. But there are clear red flags:

- Difficulty rising from a chair or getting up from the floor

- Struggling to raise your arms to brush your hair

- Neck weakness so you can’t hold your head up

- A purple or red rash on eyelids or knuckles

- Swallowing trouble-food sticks, you choke on liquids

- Constant fatigue that doesn’t improve with rest

These aren’t vague complaints. They’re specific patterns. In polymyositis, weakness is the same on both sides of the body and gets worse over weeks or months. In dermatomyositis, the rash often appears before muscle weakness, sometimes months earlier. That’s why misdiagnosis happens in nearly 3 out of 10 cases.

How Doctors Diagnose These Conditions

There’s no single blood test that confirms either disease. Diagnosis is a puzzle. Here’s how it’s solved:

- Blood tests: Elevated creatine phosphokinase (CPK)-often 5 to 10 times higher than normal-is a major clue. Other markers like ESR and CRP show inflammation. Autoantibodies (like anti-Jo-1 or anti-Mi-2) can point to specific subtypes.

- Electromyography (EMG): This test measures electrical activity in muscles. In both conditions, it shows abnormal, short bursts of activity-like a muscle firing randomly.

- MRI: Shows swelling and inflammation patterns in muscles. It helps doctors pick the best spot for a biopsy.

- Muscle biopsy: The gold standard. In polymyositis, immune cells (T cells) invade muscle fibers. In dermatomyositis, you see damage around the edges of muscle bundles (perifascicular atrophy) and inflammation around blood vessels.

Doctors also screen for cancer-especially in adults with dermatomyositis. About 1 in 5 cases are linked to hidden tumors, often in the lungs, ovaries, or colon. That’s why a diagnosis of dermatomyositis triggers a full cancer workup.

Why Treatment Isn’t One-Size-Fits-All

There’s no cure. But treatment can turn a disabling illness into a manageable one. The goal isn’t just to lower inflammation-it’s to rebuild strength and prevent long-term damage.

Corticosteroids like prednisone are the first step. Most doctors start with 1 mg per kg of body weight daily-so around 40 to 60 mg for an average adult. Within 4 to 8 weeks, you should see improvement. But steroids aren’t safe long-term. Side effects include weight gain, bone thinning (osteoporosis), diabetes, and cataracts. About half of patients on long-term steroids develop bone loss.

That’s why second-line drugs are almost always added:

- Methotrexate: Slows immune activity. Works well for both conditions.

- Azathioprine: Often used for maintenance after steroids are reduced.

- Mycophenolate mofetil: Popular for patients who can’t tolerate methotrexate.

- IVIG (intravenous immunoglobulin): Especially helpful in stubborn dermatomyositis cases. Given monthly, it can reduce rashes and improve muscle strength.

- Rituximab: A biologic that targets B cells. Shows 60-70% response in treatment-resistant cases, though it’s still used off-label.

New options are emerging. In 2023, early results from the IMACS trial showed JAK inhibitors like tofacitinib improved skin rashes by 65% and muscle strength by over half in dermatomyositis patients. Another drug, abatacept, is being tested in polymyositis and is showing promise in early trials.

The Role of Physical Therapy-Not Optional, Essential

Medicines stop the attack. But only physical therapy rebuilds what’s been lost.

Too many patients are told to rest. That’s a mistake. Inactivity leads to muscle wasting, joint stiffness, and permanent weakness. The right exercise program-low-resistance, high-repetition, guided by a therapist-can improve function by 35% to 45% in just six months.

Therapy starts early: within two weeks of diagnosis. It includes:

- Range-of-motion exercises to keep joints flexible

- Light resistance training with bands or small weights

- Balance and stair-climbing practice

- Breathing exercises if lung involvement is present

One patient in Texas, after nine months of steroid-only treatment with no improvement, added physical therapy. Within four months, she went from needing help to stand up to walking her dog daily. Her CPK dropped from 8,200 to 450.

Managing the Hidden Symptoms

Weakness isn’t the only problem. Many patients struggle with:

- Dysphagia (swallowing trouble): Affects 15-30% of patients. Can lead to choking or pneumonia. Speech therapists help with safe swallowing techniques.

- Interstitial lung disease: Seen in 30-40% of dermatomyositis cases. Causes shortness of breath. Requires lung scans and sometimes additional immunosuppression.

- Fatigue: Reported by 68% of patients in one survey. Not just tiredness-it’s a deep, bone-weary exhaustion. Energy conservation strategies and pacing help.

- Steroid side effects: Weight gain, insomnia, mood swings. Calcium, vitamin D, and bone density scans are mandatory for anyone on long-term prednisone.

One man in Ohio, diagnosed with dermatomyositis at 52, developed lung scarring. He now gets monthly IVIG and uses oxygen at night. He says, “I’m not cured. But I’m alive. And I can still read to my grandkids.”

What’s the Long-Term Outlook?

Twenty years ago, survival rates for these diseases were below 60%. Today, over 80% of patients live at least 10 years after diagnosis. Why? Earlier diagnosis. Better drugs. Aggressive rehab.

Patients who start treatment within six months of symptoms have an 80% chance of reaching low disease activity or remission. Delayed treatment? That’s when muscle damage becomes permanent.

But outcomes vary. Those with lung involvement or cancer-linked dermatomyositis face tougher challenges. And not everyone responds to the same drugs. That’s why personalized care matters.

Living With It: Real-Life Challenges

Patients report spending an average of 2.3 years and seeing nearly five doctors before getting the right diagnosis. Insurance delays for second-line drugs can take over two weeks per request. Many can’t afford the time off work or the co-pays.

Support groups make a difference. The Myositis Association’s survey of over 1,200 people found that those who joined a community were more likely to stick with treatment, report better mood, and feel less isolated.

Practical tips from those living with it:

- Keep a symptom journal-note strength changes, rashes, fatigue levels

- Use assistive tools: shower chairs, jar openers, raised toilet seats

- Ask for help. You’re not weak for needing it.

- Find a rheumatologist who specializes in myositis. Not all do.

One woman in Austin, diagnosed at 45, started a local support group. Now she helps newly diagnosed patients navigate insurance forms and therapy schedules. “I didn’t want anyone to go through what I did,” she says.

Where Research Is Headed

Scientists are now using myositis-specific antibodies (MSAs) to classify patients into subtypes-not just by symptoms, but by immune profile. This could lead to targeted therapies. For example, patients with anti-MDA5 antibodies (linked to severe lung disease) might get different drugs than those with anti-TIF1-gamma (linked to cancer).

Drug trials are expanding. New oral medications, gene therapies, and even stem cell approaches are in early testing. The European League Against Rheumatism updated its guidelines in 2023 to include antibody testing as standard-this alone could cut diagnosis time by 30-40%.

Still, funding is limited. Only 15% of rare autoimmune disease trials focus on myositis. The global market for treatments is growing, but most drugs are used off-label. Patients often pay out of pocket for IVIG or biologics.

Can dermatomyositis or polymyositis be cured?

No, there is no cure yet. But with early, aggressive treatment, most patients achieve remission or low disease activity. Many regain near-normal muscle function and live full, active lives. The goal is control-not cure.

Is dermatomyositis contagious?

No. These are autoimmune diseases, not infections. You can’t catch them from someone else. They’re caused by a mix of genetics and environmental triggers-like viruses or UV exposure-but not by germs.

Can children get polymyositis?

Polymyositis is extremely rare in children. The pediatric form is almost always dermatomyositis. Kids with muscle weakness and a rash should be evaluated by a pediatric rheumatologist immediately.

Why do I need a muscle biopsy if my blood tests are high?

High CPK can happen in many conditions-strenuous exercise, trauma, or even some medications. Only a biopsy can confirm it’s autoimmune myositis and distinguish between dermatomyositis and polymyositis. It also rules out other muscle diseases like inclusion body myositis, which doesn’t respond to the same treatments.

How often should I get my CPK levels checked?

Monthly during the first 3-6 months of treatment. Once stable, every 3-6 months. A 50% drop in CPK within 4-8 weeks signals the treatment is working. Rising levels may mean the disease is flaring or the medication needs adjusting.

Can I exercise if my muscles are inflamed?

Yes-but carefully. Rest won’t help. Gentle, guided exercise prevents muscle loss and improves circulation. Avoid high-intensity workouts or heavy weights. Work with a physical therapist who understands autoimmune myopathies. Pain during exercise is a warning sign-stop and consult your team.

Are there natural remedies that help?

No proven natural remedies can replace medical treatment. Some people find omega-3s or vitamin D helpful for general inflammation, but they don’t stop the immune attack. Avoid unregulated supplements-they can interfere with immunosuppressants or harm your liver. Always talk to your doctor before adding anything.

Next Steps If You Suspect You Have It

If you’re experiencing unexplained muscle weakness, especially with a rash, don’t wait. See your doctor. Ask for a referral to a rheumatologist. Bring a list of symptoms, when they started, and how they’ve changed.

Keep a record. Note what makes it better or worse. Track fatigue, swallowing issues, or skin changes. This helps your doctor spot patterns.

And if you’ve been told it’s “just aging” or “fibromyalgia” but you still feel wrong-push for more testing. Early treatment saves muscle. And muscle is freedom.

8 Comments

It's fascinating how the immunological architecture of dermatomyositis reveals a perifascicular targeting pattern-almost like the immune system is conducting a surgical strike on the muscle’s structural periphery. The presence of anti-Mi-2 autoantibodies, for instance, isn’t merely a biomarker; it’s a molecular signature of a specific immune phenotype. We’re no longer treating a monolithic disease-we’re decoding subtypes with precision oncology-level granularity.

And yet, the clinical translation remains painfully lagging. Why are JAK inhibitors still off-label for myositis when the data from IMACS is so compelling? Regulatory inertia is a silent killer.

Also, let’s not romanticize ‘rehab.’ Physical therapy isn’t ‘gentle exercise’-it’s neuromuscular re-education under immunosuppression. A delicate, high-stakes ballet. Most PTs haven’t been trained for this. We need specialized myositis rehab fellowships.

And don’t get me started on IVIG. $15,000 per infusion? That’s not healthcare-it’s a lottery system where your insurance tier determines your mobility.

Empathy is not a treatment modality. Rigor is.

I’ve been living with polymyositis for 7 years. The first thing I learned? Rest doesn’t heal-it atrophies. My therapist taught me to move even when it hurt. Started with 5 minutes of leg lifts in bed. Now I hike. Not because I’m strong, but because I refused to let the disease define my limits.

IVIG saved my swallowing. Steroids wrecked my bones. Methotrexate? My lifeline. It’s not perfect, but it’s mine.

You’re not alone. And you don’t have to be brave. Just consistent.

This article is a glorified pharmaceutical ad. ‘New options emerging’? More like ‘new ways to make you pay.’ IVIG costs more than my car. JAK inhibitors? Still experimental. And don’t even get me started on the ‘support groups’-they’re just echo chambers for people who can’t afford real treatment.

Doctors love to talk about ‘remission.’ What they mean is ‘we stopped the bleeding but left you with a corpse of a body.’

Save the inspirational quotes. I need a cure, not a pep talk.

I appreciate the depth of this post, but I’m troubled by the omission of socioeconomic barriers. The article mentions insurance delays and co-pays in passing-but these aren’t footnotes. They’re life-altering.

Can a single mother in rural Alabama access a rheumatologist who specializes in myositis? Can she afford monthly IVIG without losing her job? The science is brilliant-but the system is broken.

Until we address access, equity, and affordability, we’re not treating patients-we’re treating privilege.

Also: the muscle biopsy is essential. But it’s invasive, expensive, and often delayed. Why isn’t there a push for non-invasive biomarkers? Why is the gold standard still a scalpel?

Let’s not just celebrate progress. Let’s demand justice in its distribution.

Yo, I read this whole thing. You guys are overcomplicating it. It’s simple: your immune system goes rogue, you get weak, you get a rash, you get meds, you do PT. End of story.

But here’s the real issue-doctors don’t know this stuff. My sister went to five doctors before someone said, ‘Hey, maybe it’s not fibromyalgia.’

And yeah, IVIG is crazy expensive. But if you’re lucky enough to get it, DO IT. Don’t wait until you can’t lift your coffee cup. I’ve seen it.

Also, stop listening to people who say ‘natural remedies.’ You don’t cure autoimmune disease with turmeric. That’s not wisdom-that’s dangerous.

I’m a nurse who works with rheumatology patients. This post nails it. Especially the part about PT not being optional. So many patients are told to rest and then end up with contractures. It’s heartbreaking.

Also, the cancer screening point? Critical. I had a patient with dermatomyositis who was diagnosed with ovarian cancer because of it. She’s alive today because someone didn’t ignore the rash.

Just… thank you for writing this. It’s rare to see something so accurate.

As someone from India, I’ve seen how rare these diseases are here-and how little awareness exists. My cousin was misdiagnosed for 3 years. No one knew what ‘dermatomyositis’ meant. We had to order books from the US.

But even here, the basics work: steroids + PT + patience. We don’t have IVIG or rituximab everywhere, but we have determination.

And yes-support groups matter. Even if it’s just one person sharing a story in a village clinic. That’s how change starts.

Keep writing. People need to know they’re not invisible.

Thank you… for writing this… with such clarity… and care… I’ve been waiting… for someone… to explain… the difference… between polymyositis… and dermatomyositis… without jargon… and without sugarcoating…

And the part… about swallowing…? That… hit me… hard…

I’ve had this… for 11 years…

And I still… cry… when I read… something… like this…