How Generic Drugs Are Reshaping Brand Pharmaceutical Economics

Generics Are Eating Brand Drug Revenue - And That’s by Design

When a brand-name drug loses its patent, its sales don’t just dip - they collapse. Often, within a year, revenue drops by 80-90%. That’s not a glitch. It’s the system working as intended. The Hatch-Waxman Act of 1984 created a legal balance: reward innovation with patents, then let competition kick in. Generic drugs - identical in active ingredients, safety, and effectiveness - flood the market at 80-85% lower prices. And they’ve taken over. Today, generic drugs make up 90% of all prescriptions filled in the U.S., yet they account for just 20% of total drug spending.

This isn’t just about cheaper pills. It’s about a fundamental economic shift. Brand manufacturers built empires on monopoly pricing. Generics operate like commodities - the more players enter, the lower the price drops. One study found that with just three generic makers, prices fall by 20% within three years. Add five or more, and the price can plummet further. The FDA tracked 2,400 new generics approved between 2018 and 2020. Every single one undercut the brand price. That’s not luck. It’s math.

The Billion-Dollar Hit: What Happens When the Patent Expires

For brand manufacturers, patent expiration isn’t a slow fade - it’s a cliff. Take Humira, the top-selling drug in the U.S. for years. When its patent expired in 2023, sales dropped nearly 90% in the first year. Companies like Pfizer and AbbVie see their stock prices swing wildly around these dates. Investors know: when the patent dies, so does the revenue stream.

That’s why brand companies don’t just sit back. They fight. One tactic? "Pay for delay" deals. A brand manufacturer pays a generic company to hold off on launching its version. These deals cost patients and insurers billions. The Congressional Budget Office estimates these settlements add $12 billion a year to drug costs - $3 billion of it paid directly by patients. Another trick? "Product hopping". A brand company slightly changes a drug’s formula or delivery method, gets a new patent, and pushes patients to the new version - even if the old one still works. The CBO says ending this practice would save $1.1 billion over ten years.

Generics Aren’t Free - But They Should Be Cheaper Than They Are

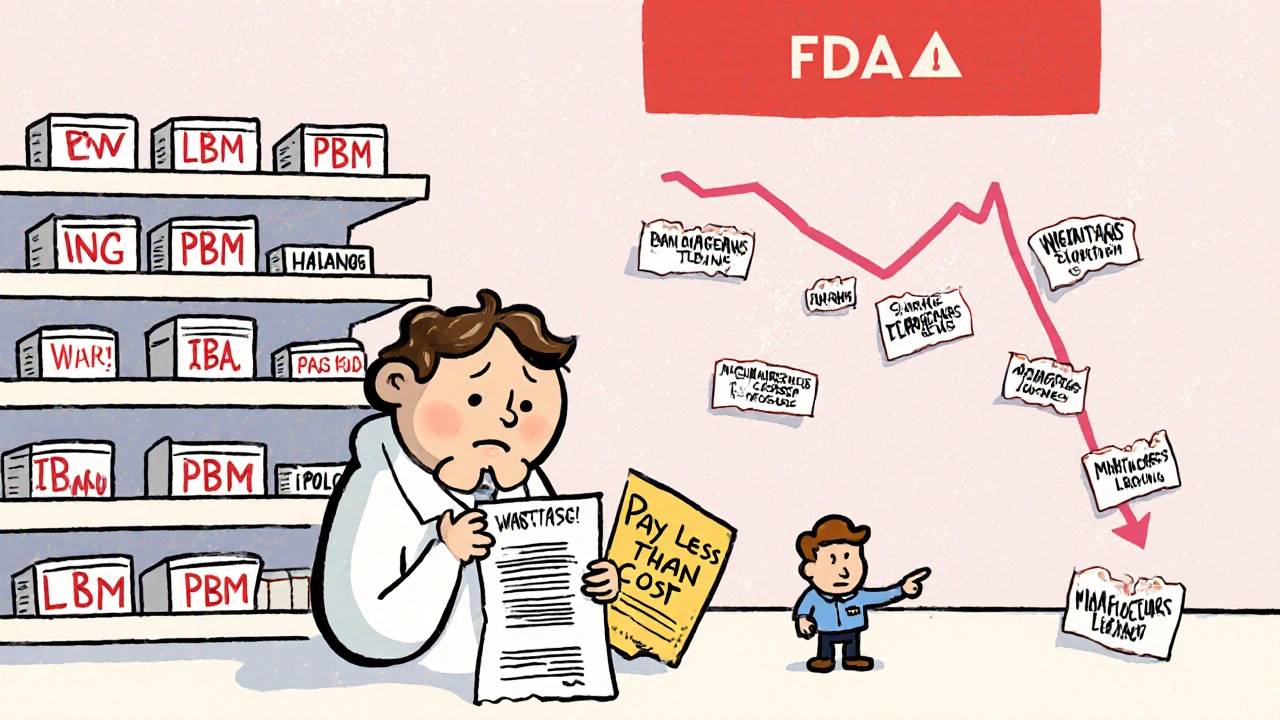

Here’s the paradox: generics save the U.S. healthcare system an estimated $330 billion a year. But patients still pay too much. Why? Because the middlemen are taking a cut. Pharmacy Benefit Managers - or PBMs - control which drugs get covered, what pharmacies get paid, and how much patients pay. They negotiate rebates with drugmakers, but rarely pass savings to consumers. A Schaeffer Center study found patients pay 13-20% more for generics than they should because of opaque PBM pricing. Pharmacists on Reddit report losing money on generic prescriptions because PBM reimbursement rates change weekly. Some pharmacies are forced to absorb the loss just to stay in network.

And it’s not just patients. Generic manufacturers are squeezed too. As competition heats up, margins shrink. Some companies cut corners on quality or shut down production entirely. That’s how you get drug shortages - not because no one can make the medicine, but because no one can make it profitably. The FDA has warned that the pressure to lower manufacturing costs may be leading to supply chain fragility.

Brand Companies Are Adapting - Or Getting Out

Some brand manufacturers are fighting to survive. Others are changing the game entirely. Novartis spun off its generics division, Sandoz, as a separate company in 2022. That let Novartis focus on high-margin, innovative drugs while Sandoz took on the low-margin, high-volume generic market. It’s a smart split - two different businesses with two different economics.

Other brands are launching their own generics - called "authorized generics". These are made by the original brand company but sold under a generic label. It’s a way to capture some of the generic market share and keep revenue flowing after patent loss. Pfizer did this with its cholesterol drug Lipitor after its patent expired. It didn’t stop the drop, but it softened the blow.

Still others are shifting focus. Instead of chasing blockbuster drugs with short patent lives, companies are investing in complex therapies - gene therapies, biologics, cancer treatments - where it’s harder and more expensive for generics to copy. These drugs aren’t just expensive; they’re protected by layers of patents and regulatory exclusivity. That’s the new frontier: innovation that can’t be easily replicated.

The Bigger Picture: Who Really Wins?

On paper, generics are a win for everyone. Patients pay less. Insurers save money. The government spends less on Medicare and Medicaid. The Congressional Budget Office calculated that in 2014 alone, generics saved the U.S. $253 billion. That’s money that could go to housing, education, or other health services.

But the system is broken in places. PBMs profit from complexity. Brand companies game the patent system. Generic manufacturers face impossible pricing pressure. And patients? They’re often caught in the middle - paying more than they should, even for cheap drugs.

There are signs of change. Bipartisan bills are moving in Congress to ban pay-for-delay deals. The FDA’s GDUFA program, funded through $1.1 billion in industry fees through 2027, is speeding up generic approvals. By 2028, an estimated $400 billion in brand drug revenue will be at risk from expiring patents. That’s a tidal wave of change coming.

Generics aren’t the enemy of innovation. They’re its necessary counterpart. Without them, drugs would be unaffordable for most. But without fair rules, the system favors profit over people. The question isn’t whether generics should exist. It’s whether we’ll fix the system so they work for everyone - not just the companies that control them.

What’s Next for the Drug Market?

The future of drug pricing won’t be decided by doctors or patients. It’ll be shaped by regulators, lawmakers, and corporate strategy. Here’s what’s likely to happen:

- More brand companies will spin off or sell their generic divisions to focus on high-margin innovation.

- Complex generics - like inhalers, injectables, and biosimilars - will grow slowly, because they’re harder to make and approve.

- Patent thickets will keep getting challenged, but companies will keep using them - until the law changes.

- Pay-for-delay deals may finally be banned, saving billions, but only if Congress acts.

- PBMs will face more scrutiny - and possibly regulation - as their role in driving up costs becomes harder to ignore.

The bottom line? Generics are here to stay. And they’re forcing the entire industry to adapt. The question is whether the system will evolve to serve patients - or keep serving profits.

Why are generic drugs so much cheaper than brand-name drugs?

Generic drugs cost less because they don’t need to repeat expensive clinical trials. The original brand company spent years and billions developing the drug and proving it’s safe and effective. Generic manufacturers only need to prove their version works the same way - a much faster and cheaper process. They also face intense competition, which drives prices down. The FDA says generics typically cost 80-85% less than the brand version.

Do generic drugs work as well as brand-name drugs?

Yes. The FDA requires generics to have the same active ingredient, strength, dosage form, and route of administration as the brand drug. They must also be bioequivalent - meaning they’re absorbed into the body at the same rate and to the same extent. Millions of people take generics every day, and they’re just as safe and effective. The only differences are in inactive ingredients, like fillers or colors, which don’t affect how the drug works.

What is the Hatch-Waxman Act and why does it matter?

The Hatch-Waxman Act of 1984 created the legal framework for generic drugs in the U.S. It let generic companies apply for approval without repeating costly clinical trials, speeding up market entry. At the same time, it gave brand companies extra patent time to make up for delays in FDA approval. This balance was meant to encourage innovation while ensuring affordable drugs later. It’s the reason generics exist today - and why brand companies lose revenue when patents expire.

Why do some generic drugs have shortages?

When too many companies make the same generic drug, prices drop so low that some manufacturers can’t cover their costs. They shut down production. If only one or two companies are left, and one has a problem - like a factory inspection failure or supply chain issue - there’s no backup. That’s when shortages happen. The FDA says this is becoming more common as profit margins shrink in the generic market.

What are "pay for delay" deals and why are they controversial?

A "pay for delay" deal happens when a brand drug company pays a generic company to delay launching its cheaper version. Instead of competing, they split the profits. This keeps prices high and delays savings for patients and insurers. The Congressional Budget Office says these deals cost billions each year. Critics call them anti-competitive. Supporters argue they’re legal settlements. But most experts agree they hurt consumers.

Why do pharmacies sometimes lose money on generic prescriptions?

Pharmacy Benefit Managers (PBMs) set the reimbursement rates pharmacies get paid for each drug. These rates often don’t match the actual cost of the drug, especially for generics. Sometimes, PBMs pay less than what the pharmacy paid to buy the drug. That means the pharmacy loses money on the sale. Many small pharmacies report this happens often, forcing them to rely on higher-margin brand drugs or other services to stay open.

Will generic drug prices keep falling?

They will - but only if competition stays high. When more companies enter the market, prices drop. But if consolidation reduces the number of manufacturers - which has happened with over 100 mergers in the last decade - prices can rise again. The FDA is trying to speed up approvals to keep competition strong, but it’s a constant battle. Prices won’t fall forever; they’ll stabilize when only a few profitable makers remain.

15 Comments

This is why I don't trust brand-name drugs anymore. I've been on generics for years and never had an issue. My blood pressure's stable, my cholesterol's down, and I'm saving $200 a month. The system works if we let it.

PBMs are the real villains here...!!!! They're not middlemen... they're VAMPIRES... sucking the life out of pharmacies and patients alike...!!! And no one's doing anything...!!!

I grew up in India where generics are the norm. We don't have the same brand worship. My mom takes the same blood pressure med her doctor prescribed 15 years ago - same pill, same results. The U.S. needs to stop treating medicine like a luxury item.

The Hatch-Waxman Act remains one of the most effective pieces of healthcare legislation in U.S. history. It balanced innovation with access. The current challenges stem not from the law itself, but from its erosion by corporate maneuvering.

wait so you're telling me that the reason my $150 brand pill is now $3 is because some guy in a lab just copied the recipe?? like... that's it?? no magic?? no secret sauce?? i feel so used

generic drugs in india cost 1/10th of usa price and still work better than some brand names here... why? because here the system is rigged... not the science

Generics save billions. PBMs take them.

It’s encouraging to see more people recognizing that generics aren’t a compromise - they’re a right. The real tragedy is how much effort goes into blocking access instead of expanding it.

I don't care how cheap it is if my insurance won't cover it. Why does it always come down to paperwork and bureaucracy? I just want my damn pills.

The whole system is a farce. Patients are the suckers. Pharma CEOs get bonuses. PBMs get rich. Generics? They're just the punchline nobody laughs at because they're too busy paying for them

I've spent years thinking about this - the emotional weight of medicine. We treat drugs like they're magical, when really, they're chemistry. The brand name is just branding. That bottle labeled 'Lipitor' and the one labeled 'atorvastatin' contain the exact same molecules. The difference is psychological, not pharmacological. And yet, we pay more for the label. We've been conditioned to believe that the name gives it power. But it doesn't. It's just a name. The real power is in the science - and that science belongs to everyone. Why should a corporation own the right to make a life-saving molecule expensive for decades? The system isn't broken - it was designed this way. And we're the ones who keep letting it happen.

The FDA's GDUFA program is the only thing keeping generic approvals moving. Without that industry fee funding, we'd be waiting 3-5 years for new generics. Congress needs to renew it without delays. This isn't politics - it's public health.

The structural inefficiencies in the generic supply chain are a classic example of market failure driven by oligopolistic consolidation. When the number of manufacturers falls below the critical threshold for price elasticity, we observe non-competitive pricing dynamics - even in commoditized markets. This necessitates regulatory intervention to restore allocative efficiency.

I'm from the UK - we have generics too, but the NHS negotiates prices centrally. No PBMs. No rebates. No games. The price is set, and everyone pays it. I know it's not perfect, but at least no one goes broke buying insulin.

I work in a pharmacy in Delhi and we sell the same generic as the one in the US for 50 cents. The difference isn't in the pill. It's in the system. We need to fix the system, not blame the pills.