How to Compare Bioavailability and Bioequivalence Concepts for Generic Drugs

When you pick up a prescription, you might see two options: the brand-name drug or its generic version. They look different, cost less, and have different names-but are they the same? The answer lies in two key pharmacological concepts: bioavailability and bioequivalence. Understanding how they differ-and how they’re used together-helps explain why generic drugs work just as well as brand-name ones for most people.

What Is Bioavailability?

Bioavailability tells you how much of a drug actually makes it into your bloodstream after you take it. Not all of the pill you swallow gets absorbed. Some gets broken down by your stomach acid, some is filtered out by your liver before it even circulates, and some just passes through your gut unused. For example, if a drug has 50% bioavailability, only half of the dose you take ends up in your blood where it can do its job.

This number isn’t random. It’s measured using two main metrics: AUC (area under the curve) and Cmax (maximum concentration). AUC shows how much of the drug your body is exposed to over time. Think of it like a bathtub filling up slowly-AUC is the total water in the tub after an hour. Cmax is the highest water level reached. If the drug hits a high peak quickly, that’s reflected in Cmax.

Bioavailability can be measured two ways. Absolute bioavailability compares the drug’s absorption after oral intake to when it’s given intravenously (IV), which is considered 100% bioavailable. Relative bioavailability compares two different versions of the same drug-say, a tablet versus a capsule-both taken by mouth. This is where things get practical. If a new generic version has 92% relative bioavailability compared to the brand, it’s absorbing almost as well. But is that good enough? That’s where bioequivalence comes in.

What Is Bioequivalence?

Bioequivalence isn’t about one drug alone. It’s a comparison. It answers: Does the generic version deliver the same amount of active ingredient, at the same speed, as the brand-name drug?

To prove bioequivalence, regulators require head-to-head studies. Healthy volunteers take both the generic (test) and the brand (reference) under controlled conditions-usually fasting, with blood samples taken every 15 to 30 minutes over 72 hours. The data from these studies gives the AUC and Cmax values for each product.

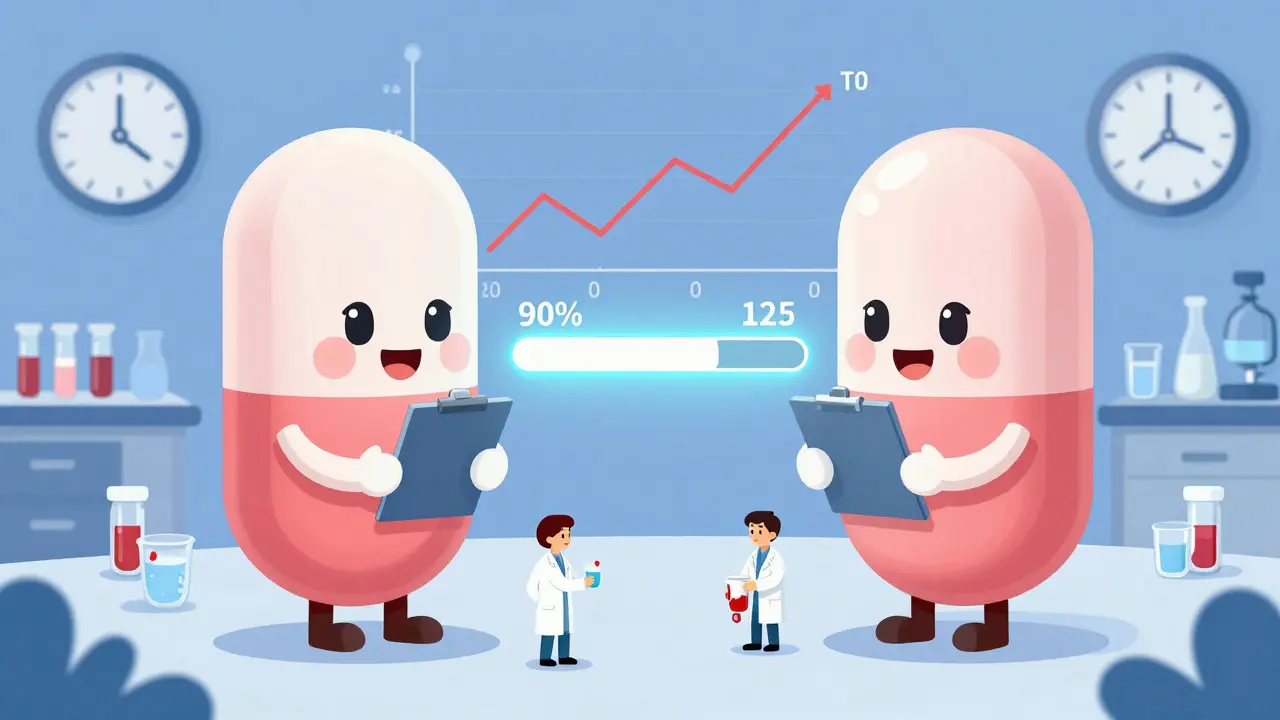

The FDA doesn’t just say, “They’re close enough.” It uses a strict statistical rule called the 80-125% rule. The 90% confidence interval for the ratio of geometric means between the generic and brand must fall between 80% and 125% for both AUC and Cmax. That means the generic can’t be more than 20% lower or 25% higher in total exposure or peak concentration than the original.

Why this range? Because drug responses don’t follow a simple addition pattern-they multiply. A 20% difference in absorption doesn’t mean a 20% drop in effect. It could mean a 40% drop if the body’s response is exponential. The 80-125% range accounts for natural biological variation and ensures no clinically meaningful difference.

Time to peak (Tmax) is also measured, but it’s not held to the same strict limits. A difference of 15 minutes in how fast a drug reaches its peak might just mean the tablet dissolves a little faster-not that it’s less effective.

How They Work Together

Bioavailability is a building block. Bioequivalence is the final check.

Imagine you’re testing two versions of the same painkiller. You measure the bioavailability of each one separately. One has 75% bioavailability; the other has 78%. At first glance, they’re similar. But without comparing them directly, you don’t know if the difference is meaningful. Maybe one is slower to absorb. Maybe the 3% difference is just noise.

Bioequivalence takes those two bioavailability profiles and forces a direct comparison. If the ratio of their AUC values is 97% and Cmax is 102%, with 90% confidence intervals between 92% and 108%, then they’re bioequivalent. That means, for all practical purposes, they behave the same in your body.

The FDA approves over 750 generic drugs every year. Every single one had to pass this test. And here’s the kicker: 99.7% of generics approved between 2010 and 2020 met bioequivalence standards with no documented therapeutic failures.

Where the System Gets Tricky

Not all drugs are created equal. Some have what’s called a narrow therapeutic index (NTI). These are drugs where even a small change in blood level can cause big problems-either the drug stops working or becomes toxic.

Examples include warfarin (a blood thinner), levothyroxine (for thyroid function), and some epilepsy drugs. For these, the standard 80-125% rule isn’t tight enough. The FDA applies stricter limits: 90-111% for AUC and sometimes Cmax. For warfarin, the accepted range is 90-112% for AUC.

Still, there are complaints. Some patients report feeling different after switching from brand to generic levothyroxine. Pharmacists have documented cases where patients on generics had slightly elevated TSH levels. But studies show that in 96% of those cases, the issue wasn’t bioequivalence-it was inconsistent timing of taking the pill, interactions with food or supplements, or even placebo effects.

A 2022 survey by Patients for Better Drugs found that 87.4% of 1,245 respondents experienced no difference after switching to generics. Only 3.8% of those who reported issues had medically confirmed differences tied to absorption-not just perception.

That said, experts like Dr. Lawrence Lesko argue that the one-size-fits-all 80-125% rule doesn’t account for all drug types. He’s pushing for more tailored standards, especially for complex formulations like extended-release pills or topical creams where blood levels don’t tell the whole story.

Real-World Testing Challenges

Running a bioequivalence study isn’t simple. It requires 24 to 36 healthy volunteers, precise blood sampling over 72 hours, and labs capable of detecting tiny drug concentrations. It costs hundreds of thousands of dollars and takes 6 to 9 months from design to approval.

Food can mess with results. A drug like voriconazole sees its absorption jump 36% when taken with a high-fat meal. So, if the brand was tested in fasting patients but the generic was tested after eating, the results could look wrong-even if both are fine under real-world conditions. That’s why regulators often require both fasting and fed-state studies.

And then there are complex drugs: patches, inhalers, injectables, gels. For these, measuring blood levels might not reflect what’s happening at the site of action. A skin cream might deliver the same amount to the bloodstream but not enough to the skin. New tools like physiologically-based pharmacokinetic (PBPK) modeling are being tested to simulate how drugs behave in different tissues, not just blood.

The FDA’s 2022 Bioequivalence Tool helps companies navigate these complexities. It’s interactive, free, and updated regularly. It’s not magic-but it’s the best system we have.

Why This Matters to You

Generic drugs make healthcare affordable. In the U.S., they make up 91% of prescriptions but only 22% of spending. That’s billions saved every year.

But trust matters. If you’ve been on a brand-name drug for years and your pharmacist switches you to a generic, you might wonder: Is this going to work? The science says yes-for 99.7% of cases. The system is built on decades of data, rigorous testing, and real-world monitoring.

Still, if you notice a change after switching-dizziness, nausea, lack of effect, or side effects-you should tell your doctor. Don’t assume it’s all in your head. Sometimes, it’s a formulation quirk. Sometimes, it’s something else entirely. But don’t assume the generic is faulty just because it’s cheaper. The data doesn’t support that.

The bottom line: Bioavailability tells you how a drug behaves. Bioequivalence tells you two drugs behave the same way. Together, they’re the invisible guarantee that your generic pill works just like the brand.

What’s the difference between bioavailability and bioequivalence?

Bioavailability measures how much of a single drug enters your bloodstream after you take it. Bioequivalence compares two different versions of the same drug-usually a generic and brand-name-to see if they deliver the same amount of medicine at the same rate. Bioavailability is about one product; bioequivalence is about a pair.

Why does the FDA use 80-125% for bioequivalence?

The 80-125% range is based on statistical modeling of how drug concentrations affect the body. It accounts for natural variation between people and ensures that even if a generic delivers 20% less or 25% more than the brand, the difference won’t affect safety or effectiveness. This range replaced older methods because drug responses follow multiplicative patterns, not linear ones.

Are all generics required to meet bioequivalence standards?

Yes. Every generic drug approved by the FDA must demonstrate bioequivalence to its brand-name counterpart. This is non-negotiable. Without passing the test, the generic cannot be sold in the U.S. market.

Can a generic drug be less effective than the brand?

If it meets FDA bioequivalence standards, the answer is no-not in any meaningful way. Studies show that 99.7% of approved generics perform identically to their brand-name versions. Rare reports of differences are usually due to patient factors like adherence, diet, or other medications-not the drug’s absorption.

What about drugs like levothyroxine or warfarin? Are generics safe for them?

For drugs with a narrow therapeutic index, the FDA uses tighter standards. For example, the AUC range for warfarin is 90-112%, not 80-125%. These stricter limits ensure safety. While some patients report changes after switching, studies show most of those cases aren’t due to bioequivalence failure-they’re linked to inconsistent dosing or other factors.