Wholesale Economics: How Generic Drug Distribution and Pricing Really Work

When you buy a generic pill at the pharmacy, you probably think the price is set by the manufacturer. But the real story happens behind the scenes - in the hands of a few giant wholesalers who control how much those pills cost before they even reach your local drugstore. The system isn’t broken. It’s working exactly as designed. And for the companies running it, generic drugs are the most profitable part of the entire pharmaceutical supply chain.

Who Controls Generic Drug Prices?

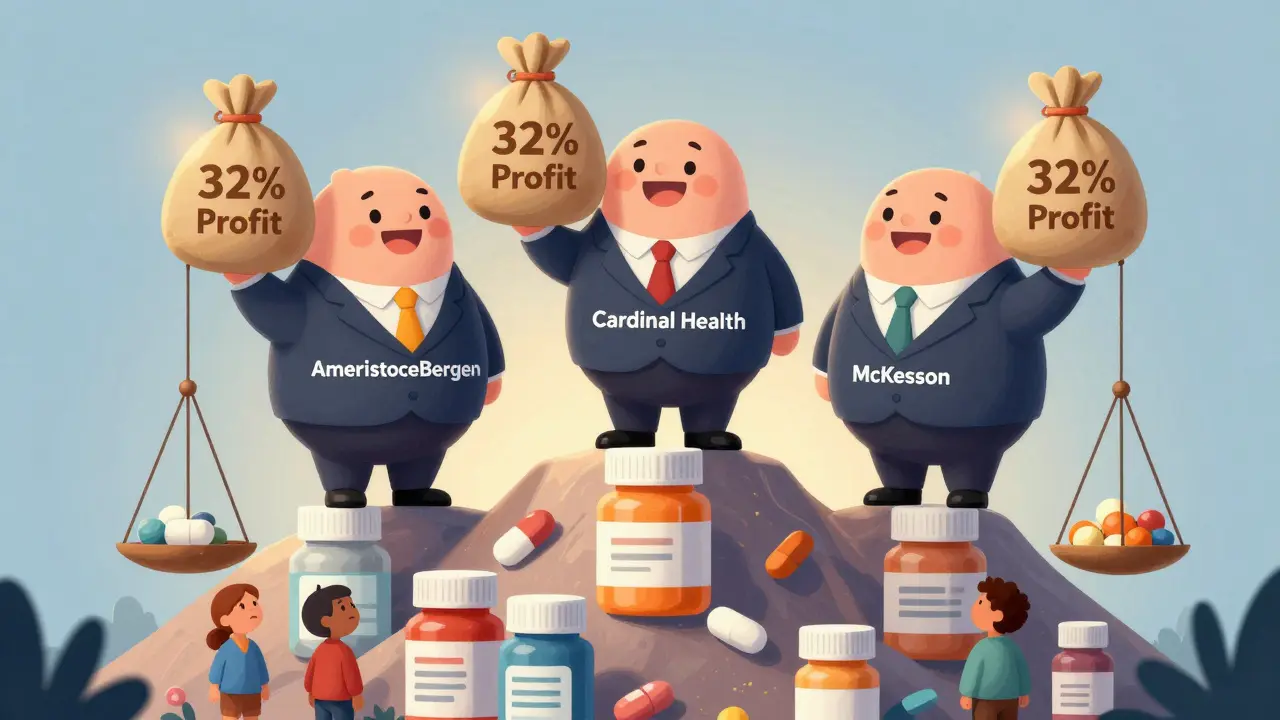

Three companies - AmerisourceBergen, Cardinal Health, and McKesson - handle about 85% of all prescription drugs distributed in the U.S. They don’t make the pills. They don’t sell them to you. But they control the flow. And they make more money on generic drugs than on brand-name ones, even though generics make up a smaller slice of total sales. In 2009, generics accounted for just 9% of wholesale revenue. But they brought in 56% of the gross profits. That’s not a typo. Wholesalers made eleven times more profit per dollar spent on generics than on branded drugs. For every $100 spent on a brand-name drug, wholesalers made about $3 in profit. For every $100 spent on a generic, they made $32. That’s the core of wholesale economics in generic drugs: low volume, high margin.Why Are Generics So Profitable for Wholesalers?

It comes down to bargaining power. Generic drugmakers compete fiercely. There are dozens of companies making the same pill - metformin, lisinopril, atorvastatin - and they all need to get their product into the hands of pharmacies. To win contracts, they slash prices. That leaves wholesalers with huge room to mark up the price without raising eyebrows. Branded drugmakers, on the other hand, have patents, marketing muscle, and patient loyalty. They don’t need to bargain. They set the price, and wholesalers take what’s offered. But with generics, it’s the opposite. Wholesalers hold the cards. They can demand lower prices from manufacturers, then sell at a much higher markup to pharmacies. That’s why the gross margin for manufacturers on generics is only 49.8% - far below the 76.3% they make on branded drugs. But for wholesalers? Their gross margin on generics is significantly higher, even if their net profit per unit is thin.How Pricing Actually Works: Tiered, Not Fixed

Wholesalers don’t use one price for everyone. They use tiered pricing - a system designed to push pharmacies into buying in bulk. Here’s how it works:- Orders under 100 units: $10 per pill

- Orders over 100 units: $8 per pill (20% discount)

- Orders over 500 units: $7 per pill (30% discount)

Generics vs. Brands: The Profit Flip

The numbers tell a clear story:| Entity | Brand-Name Drug Profit per $100 Spent | Generic Drug Profit per $100 Spent |

|---|---|---|

| Manufacturer | $58 | $18 |

| Wholesaler | $3 | $32 |

| Pharmacy | $3 | $32 |

| PBM (Pharmacy Benefit Manager) | $10 | $40 |

Why This System Still Exists

You might wonder: why hasn’t this changed? Why don’t pharmacies just buy directly from manufacturers to cut out the middleman? Because they can’t. Not easily. The system is built on logistics, not just price. Wholesalers don’t just deliver pills. They handle inventory management, regulatory compliance, recalls, returns, and emergency shipments. A pharmacy doesn’t want to deal with 20 different manufacturers. They want one supplier who can deliver hundreds of drugs on one truck, on schedule, every time. Plus, the Big Three have deep relationships with insurers, PBMs, and government programs like Medicaid. They’re embedded in the system. Even if a new wholesaler tried to enter the market, they’d struggle to compete with the scale, technology, and contracts the big players already have.The New Wild Card: Drug Shortages

The stability of generic drug pricing cracked in 2023. After years of falling prices - a deflationary trend that began in 2021 - shortages started popping up. One factory shut down. A key ingredient became hard to source. A manufacturer stopped making a low-margin drug. Suddenly, the supply of a common generic like doxycycline or levothyroxine dropped. Demand didn’t. Prices spiked. Wholesalers raised prices. Pharmacies passed it on. Patients paid more. These shortages aren’t random. They’re predictable. When a generic drug’s price falls too low, manufacturers stop making it. They focus on more profitable products. The market corrects - but only after a shortage hits. Then, prices jump. And the cycle repeats.

What Can Be Done?

Experts agree: the system works too well for the middlemen. The USC Schaeffer Center found that more than $1 in every $5 spent on prescription drugs goes to distribution profits. That’s not necessarily bad - logistics cost money. But when wholesalers make eleven times more on generics than on brands, it raises questions. Some solutions are already being tested:- More transparency in pricing - knowing exactly what each player earns

- Encouraging new wholesalers to enter the market

- Direct purchasing by large hospital systems

- Government oversight of pricing during shortages

What This Means for You

If you’re a patient, you’re seeing the results: generic drugs are cheaper than brands - but not as cheap as they should be. If you’re a small pharmacy, you’re stuck paying inflated prices because you can’t buy in bulk like a chain. If you’re a policymaker, you’re watching a system where profit incentives are misaligned with patient access. The truth is simple: generic drugs aren’t cheap because manufacturers are efficient. They’re cheap because the system forces manufacturers to compete on price. But the real winners? The ones who control the pipeline.Frequently Asked Questions

Why are generic drugs cheaper than brand-name drugs if wholesalers make more profit on them?

Generic drugs are cheaper because manufacturers sell them at rock-bottom prices to win contracts. Wholesalers and pharmacies then mark them up significantly - but the final price is still lower than branded drugs because the original manufacturing cost is much lower. The profit isn’t in the sticker price - it’s in the volume and the gap between what manufacturers charge and what wholesalers charge.

Do wholesalers cause drug shortages?

They don’t cause them directly, but they contribute. When generic drug prices fall too low, manufacturers stop making them because it’s not profitable. Wholesalers don’t stockpile drugs in anticipation of shortages - they buy based on demand. So when a manufacturer exits the market, the wholesaler can’t fill the gap. The shortage hits pharmacies and patients first.

Why don’t pharmacies buy directly from manufacturers?

It’s logistically impossible for most. A single pharmacy might need hundreds of different drugs from dozens of manufacturers. Managing that many suppliers, tracking expiration dates, handling returns, and meeting regulatory requirements would be overwhelming. Wholesalers consolidate all of that into one order, one invoice, one delivery.

Is tiered pricing fair to small pharmacies?

It’s not designed to be. Tiered pricing rewards volume. Small pharmacies can’t buy 500 units of every drug. So they pay more per unit. That’s why independent pharmacies often have thinner margins than big chains. It’s a structural disadvantage built into the system.

Can anything be done to lower generic drug prices?

Yes - but it requires systemic change. More competition among wholesalers, transparency in pricing, and government intervention during shortages could help. Some states are experimenting with direct purchasing programs for public hospitals. But until the Big Three face real competition, prices will stay high relative to manufacturing cost.

12 Comments

So the real villains aren't the pharma giants, it's the middlemen who just move boxes and make 11x more profit than the people who actually make the pills? Wild. Feels like the whole system is rigged to reward logistics over innovation.

I work at a small clinic and this explains why our generic prescriptions keep going up even when the meds are 'cheap'. We can't buy in bulk like CVS so we're stuck paying more per pill. It's not about cost - it's about power.

It's fascinating how the profit distribution flips entirely between branded and generic drugs. Manufacturers lose out on generics, but everyone downstream - wholesalers, PBMs, even pharmacies - suddenly profit more. The system isn't broken, it's optimized for extraction, not access. And we're all just collateral in that optimization.

OF COURSE they make more on generics - it's the perfect scam. Low-cost product, zero brand loyalty, tons of competitors begging for shelf space. Wholesalers just sit there like vultures waiting for the carcass to drop. And you think you're saving money? Nah. You're just feeding the machine.

tiered pricing is just a trick to make small pharmacies buy more than they need then get stuck with expired meds

The data is clear. Wholesalers are the real profiteers. No one talks about this because they're not drug companies. They're just middlemen. But they make more profit than the people who create the drugs. That's not capitalism. That's rent-seeking.

Why hasn't anyone broken this oligopoly? If PBMs and hospitals could bypass the Big Three, wouldn't that force prices down? The infrastructure argument feels like a smokescreen. If they can handle 85% of the market, they're not fragile - they're entrenched. And that's the real problem.

I think the real issue is that we treat medicine like a commodity instead of a public good. The fact that a life-saving pill can be held hostage by inventory tiers and pricing games is horrifying. We need to stop pretending this is just business - it's healthcare.

Big Pharma and Big Wholesalers are the same thing. They're all connected. The whole system is a pyramid scheme disguised as healthcare. The shortages? Planned. The price spikes? Engineered. They want you dependent. They want you paying more. They want you too scared to question it.

It's not merely a failure of market structure - it's a moral collapse. When the distribution chain earns more than the producers, we have abandoned the very principle of value creation. We are no longer rewarding innovation or labor; we are rewarding monopolistic control over essential human needs. This is not capitalism - it is feudalism with corporate logos.

generics are cheap because no one wants to make them anymore

There's hope. More hospitals are starting direct buys. States are testing transparency laws. It's slow, but change is coming. We just need to keep pushing for systems that reward access over profit. We can fix this - together.